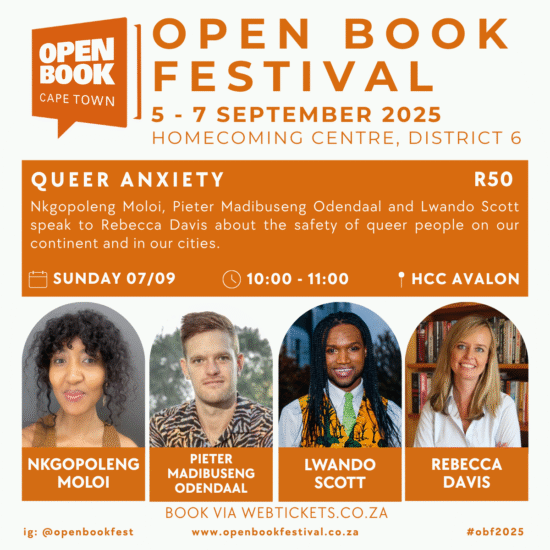

OPEN BOOK FESTIVAL PREVIEW: Dr Lwando Scott on Queer Anxiety.

This September, the Open Book Festival returns to Cape Town for three days of conversation, connection, and literary exploration. Since 2011, the Festival has carved out space for dialogue that is as urgent as it is creative, tackling the issues that shape our lives today, and, of course, issues that affect queer lives.

“I've been involved in the Open Book Festival from the start in 2011. In that time, I have lost track of the number of conversations - many of which are intersectional - that we have planned that have highlighted challenges faced by the queer community. There are times where I wonder whether another conversation is what is needed. But then I think about the value of gathering. The strength one finds in community. The necessity of that if one is going to survive. It's very easy to feel alone, to feel isolated, and to feel helpless. What I hope results from this kind of conversation - apart from the sense of community - is a clearer understanding of the diverse realities faced by people, and what one is able to do to support and assist those whose safety is most under threat,” says Frankie Murrey, the Coordinator and Curator of Open Book Festival.

For a programme titled Queer Anxiety, Nkgopoleng Moloi, Pieter Madibuseng Odendaal and Lwando Scott will speak to Rebecca Davis about the safety of queer people on our continent and in our cities

SCAFFOLD’s editor-in-chief, Gary Hartley, had a chat with Dr Lwando Scott for an exclusive preview.

What does the idea of “safety” mean to you, both personally and within a broader queer context?

For me, safety is about having the chance to have a liveable life. A liveable life remains elusive for many in post-colonial Africa, indeed, post-apartheid South Africa. By liveable life I am thinking alongside Nussbaum’s (2003) idea of capabilities as fundamental entitlements. Capacities are about freedom to be able to live, freedom to pursue one’s dreams and to live a full life without violence. Nussbaum’s (2003) articulations on “life” and “bodily integrity” amongst other capabilities are crucial in ensuring not just human rights but human capabilities. For Nussbaum (2003) “being able to live to the end of a human life of normal length; not dying prematurely, or before one’s life is so reduced as to be not worth living”. For me this is linked to the idea of safety, because the violence that is visited upon queer people in South Africa, and other parts of the African continent renders their lives unlivable, therefore unsafe.

How might open conversations about safety shift the ways communities build trust and solidarity?

I think conversations about safety from the onset need to be about our concern for the safety of all those vulnerable in our societies. Often, as queer people we face violence, and therefore start feeling unsafe, from the most intimate of spaces, our families, and this often pushes us to seek love in other places. If we are fortunate, we find that love elsewhere, but many do not, and are faced with a hard queerphobic world. Hence, for me, the conversation about safety has to be a concern about the safety of all children regardless of gender and/or sexual identity. Our concerns about the safety of girls and women in our society, intrinsically should be a concern for all kinds of women, including lesbian women, transgender women, poor women, rural women. If our societies are concerned with the safety of all the vulnerable, solidarity is built into the very framework with which we think about safety because safety is not reserved for some but for all those vulnerable.

From your perspective, what everyday spaces or situations hold the most challenges for queer people, and why?

There are many spaces that remain unsafe for queer people. There are also many spaces that are green zones for queer people. There are family homes where parents or guardians make the decision to educate themselves, seek advice, and get counselling about their gender non-conforming child and create a space for that child to be. There are parents or guardians who excommunicate their children when they learn they are queer. These are different responses from the primary environment that will have a different impact and outcome for the young people in question. So, there are challenges everywhere, but there are also incredible green zones that are fertile with empathy, understanding, the desire for education, and the understanding that in the new South Africa we all deserve not only a life full of dignity, but one that is liveable.

What do you think it takes for dialogue to move beyond awareness and into meaningful change?

I really believe in the power of education. There’s the much quoted Nelson Mandela quote about education being the most powerful tool to change the world. Perhaps corny, but this is true, which is why fascist and authoritarian governments often target education systems and institutions for destruction or manipulation, because education changes how we see, therefore how we act. Here, education is not only the ability to read a book or do maths, which are important, of course, but it is the training of the mind to be critical, to have a point of view that is informed by multiple, perhaps disagreeing sources, where you are forced to weigh the ethical standpoint. Furthermore, education has to encompass the training of the senses as well, therefore art becomes important. To think, to feel, to be, with art, is crucial for challenging the status quo, creating dialogue and ultimately creating a healthy society. This makes spaces like the Book Lounge, and the Open Book Festival indispensable in the making of a new South Africa, spaces that create avenues for the cultivation of a liveable life.