OPEN BOOK FESTIVAL PREVIEW: Dr Azille Coetzee on Queering Intimacy.

Returning to Cape Town from 5–7 September 2025, the Open Book Festival offers over 100 events featuring writers from South Africa and beyond. This year’s programme moves between the deeply personal and the globally political, with conversations on mental health, evolving identities, colonial legacies, and many more. The festival also features queer-focused programmes.

“Open Book has from the start prioritised creating a space that is inclusive, where people feel seen, safe and able to breathe out. The Festival is a time where we can celebrate each other's stories, and where we can engage and better understand each other's lived realities. As we see rights rolling back, it has become even more important for us to amplify queer voices, as well as those of other communities facing extraordinary challenges,” says Frankie Murrey, Coordinator and Curator of Open Book Festival.

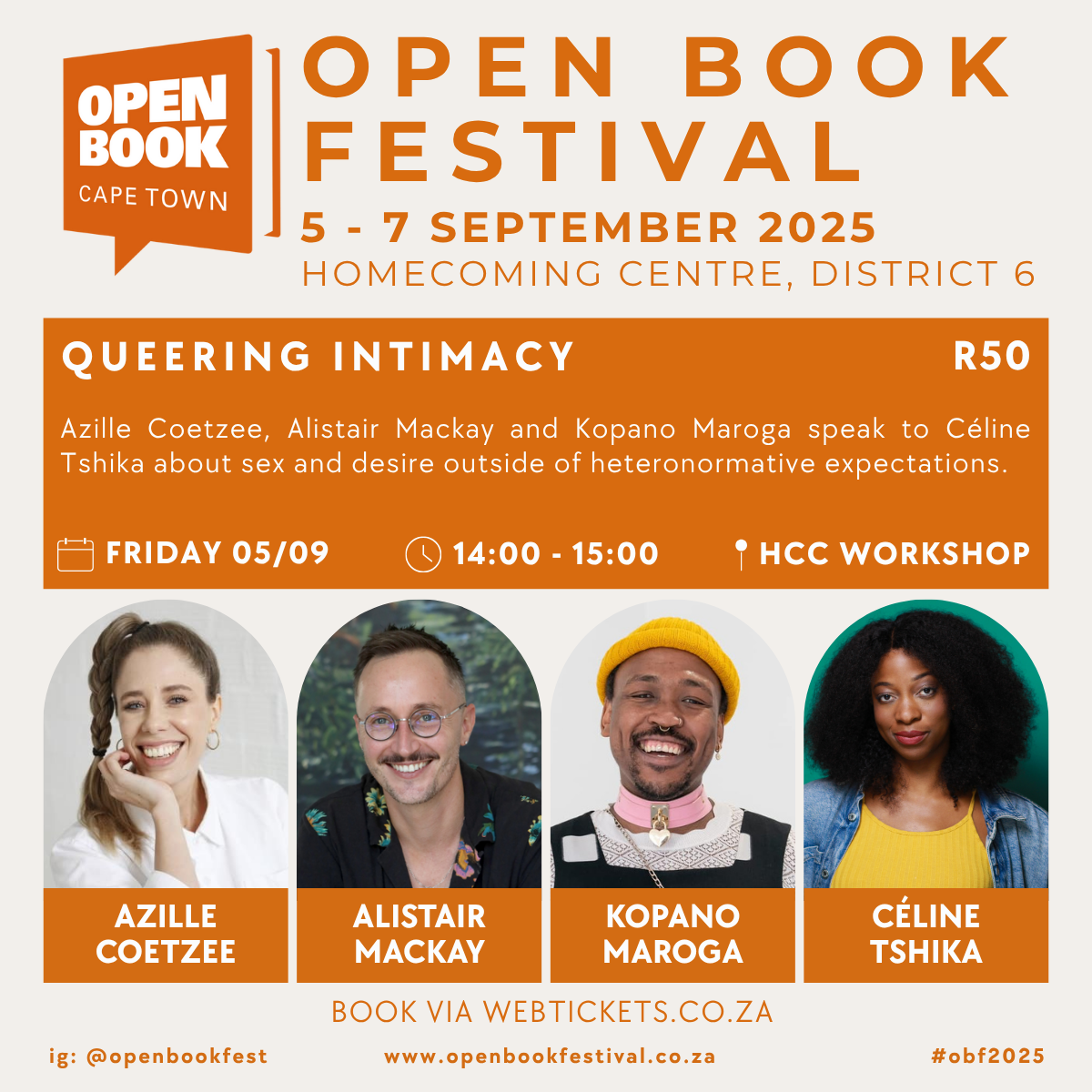

One of the festival’s queer-focused discussions is called Queering Intimacy, which invites audiences to think beyond heteronormative ideas of sex and desire, imagining new possibilities for connection and closeness.

“I think like with all Open Book events, people will leave with insights into both their own and others lives - in this case, intimate lives. We live in a country where intimate spaces are often ones of violence as well, and through conversations such as this one, I hope some of what happens is that we learn how to shift away from that. I think it also opens the definition of what intimacy can look like or mean in exciting and useful ways, allowing everyone to broaden how intimacy is integrated into our lives,” adds Murrey.

Authors Alistair Mackay, Kopano Maroga and Dr Azille Coetzee will unpack and discuss this thought-provoking topic with Céline Tshika.

Our editor-in-chief, Gary Hartley, caught up with acclaimed author and academic Dr Azille Coetzee to get some insight on intimacy without limits, and the possibilities that open up when we step outside heteronormative frameworks.

What does intimacy mean to you when freed from the heteronormative expectations or labels?

I think heteronormative conceptions of intimacy are closed off or predetermined to an extent, it follows a very specific script that you get taught from a very young age. For example, the heteronormative paradigm assigns very specific gender roles to people, and there is a plot and a timeline that we all know and that must be followed. You know exactly what to do, and if you do it well, society rewards you in many ways. When we work to free intimacy from these scripts, roles, timelines and structures it can become an exploratory endeavour that opens you up to the world and to yourself and to others in new ways. I find that queer intimacy provides me with the space to repeatedly ask anew in relation to others: who am I? And who are you? What do we want?

How can broadening our ideas of intimacy change the ways we connect with others in everyday life?

Intimacy exists everywhere, it is not just something between lovers and it is not always sexual – we experience it among friends, sometimes in relation to strangers at unexpected moments, also in familial relationships. Intimacy is often closely related to the care that we give and receive in many different contexts. Taking these different kinds of intimacy seriously, allows us to think of our lives in relation to bigger communities of care. And this means a bigger, richer life with others.

In what ways do societal norms shape — and sometimes limit — our understanding of desire, especially for queer people?

Desire is not simply something that comes from inside of us in an instinctual or “natural” way. Rather, we are trained by society into certain ways of desiring, or our desire is shaped and angled in certain directions. By our parents, by the stories that circulate in our cultures, film, television etc. For example, as a woman you get taught from a very young age that your wedding day will be the most special day of your life when you feel like a princess in a white dress, and what you must do is to find the right man to marry. As a white Afrikaner woman I was taught by the entire culture that an attractive man is one who is white and Afrikaans and adheres to certain “standards” of masculinity. In this sense desire is undeniably political and we get trained into it to a large extent. But then of course our desires also manage to escape and subvert these strictures, and that is when we have the chance to change the lives we are living and the stories we tell.

What kinds of conversations about closeness and connection do you feel are missing from the public sphere?

I think most of the conversations about closeness and connection that we see in the public sphere centre around romantic love and the nuclear family, and then these conversations are inevitably informed by heteronormative assumptions and rules (the privatised nuclear household, compulsory procreativity, monogamy, patriarchy). I am interested in conversations about the closeness and connection that we share in larger networks of people, for example the closeness we have to our friends, or our communities, or the possibilities for solidarity and connection with strangers with whom we share spaces. This is part of the conversation about queer intimacy because at stake is closeness and care that do not follow a straight line, that are not limited to the relationship between husband and wife; intimacy that veers off script.