“I am queer. I am Xhosa. I am an artist. I am a son. I am a brother. I am a change agent. I am all of those things at once, and they cannot be looked at in isolation.”-Bongani Njalo

Bongani Njalo

Fine Artist / Performance Artist / Curator/ Activist

Pronouns: He/Him

I was born in Port Elizabeth and grew up in Kwa-Dwesi, with my grandmother being the most formidable figures of my upbringing. Some of my earliest memories are of the warmth and love in my grandmother’s home where I was raised. This home was shared with my aunt (mom’s only sibling) as well as my grandmother’s sister who reared me. My parents weren’t married until I was about eight years old, and only then did I start living with them full-time. My maternal grandmother meant the world to me and everything I did was an attempt to get her approval or attention. I once made her a bowl for Mother’s Day as part of a school project in the art/craft class and she kept it safely until she died. It was a terribly ugly thing with colours all wrong and badly painted flowers on it, but she treasured it, and it only hit me after she died that she’d kept it with her all those years when I found it in her house.

What were some of the most formative experiences of your childhood?

Before she died, my grandmother always bought me a watch on my birthday, which is on the 13th of December. Every year until my late teens, she would get me a new watch and I always lost them along the year ahead or a friend would break the strap while we were playing so that’s why they had to be replaced annually.

At the beginning of every year she would promise me that she would buy me a watch for my birthday and she would take me to all the shops in the mall to pick my own watch. She would never allow anyone, particularly my mom, to sway with my decision-making. The only promise on my end was that I would pass every subject on my report.

However…

I reached a point in my childhood where it hit me that I had to conform to societal and behavioural expectations around my boyhood/masculinity and that there was something “wrong” with the way I spoke, walked and acted in my mannerisms. At the time, I never associated this with an attraction to boys or girls or intimacy. It was the constant reminders from family and friends that I was different and that “boys don’t talk with their wrists like that”, which was an unconscious part of my behaviour. As we moved from one house to the other and I changed schools only once in my life before starting high school - I knew more and more boys of different ages and races, but none of them seemed to have been openly confronting some of the issues I was dealing with like being teased for “walking like a girl”, etc., and this resulted in a quiet self-loathing and loneliness that developed without my knowing and in hindsight, I’m pretty sure it’s the reason I became such an angry teenager. I got into a lot more fights in high school than I needed to, often to try and prove a point or defend my masculinity in some twisted form or another.

I read in an interview that you grew up with very traditional parents- can you shed some light on that?

Although I’ve spent my entire life in mixed race schools and settings, my parents have always understood that there’s a form of education that is necessary for every African child, and that is the education and knowledge of one's history, heritage and ancestral spiritual practices. As a first-born son, it is my “responsibility” in African culture to ensure that the rites and rituals of my ancestors are kept alive and passed on through to the next generation(s). My father has always tried to ensure that I understand the importance of a Western education in the world we live in and find ourselves. Nevertheless, that should never be used as a means to look down upon or shun my identity as an African man. African spirituality is what grounds us and it is based on centuries of wisdom about agriculture, anthropology, medicine and even fashion, and we use African spirituality for healing and improving our daily lives by appreciating nature and bringing ourselves closer to God.

“African spirituality is what grounds us and it is based on centuries of wisdom about agriculture, anthropology, medicine and even fashion, and we use African spirituality for healing and improving our daily lives by appreciating nature and bringing ourselves closer to God. ”

School always seems to be a contentious topic, especially for LGBTIAQ+ children. What was your experience like?

As most kids do, I lived in a bubble of perfection and fantasy because I didn’t know any better. But the way other kids (boys in particular) treated me, made me realise that I was different and not like other boys. My earliest memory of othering was set in Sub A (Grade 1) where I became very close friends with Lutho John. He lived in a distant part of the same neighbourhood as I did and was also my classmate and we travelled to school together in this kombi that would pick us up and drop us all off at our respective homes daily. Anyway, Lutho and I were both fairly effeminate boys, and we gravitated towards each other because we weren’t quite as aggressive as the other boys on the playground. It was through this friendship and how other children responded to us that I learnt the word ‘moffie’ and although I didn’t understand what it meant. I knew it was wrong and it made me feel different and dirty. I remember other boys being very mean about us having “floppy wrists”, “talking like girls” or walking funny. This led to some bullying on the playground by other boys and I then started noticing that I didn’t really like or know how to play soccer like everyone else. The running, sweating, kicking and chasing seemed pointless and unnecessary to me, which led to more intimidation and bullying, so I quit altogether. It didn’t help that I was a very shy kid who would burst into tears for orals, on top of all this. The teasing was relentless, and over time I learnt to retreat into my imagination, but not without getting into a few fist fights with other boys. My most profound memory was a note that went home to my mother about one of my fights and when she confronted me about it, I told her that I’d been pushed around by another kid. I thank her response to this. She told me that she would unfortunately not be able to stand up for me every time I got into a fight all my life and that I should learn to stand up for myself and fight with all that I’ve got because bullies are generally scared of you and that I should never go down without getting in a few of my own punches to teach them to get away from me. Had she not told me this, the bullying would have carried on for longer and I know I would have managed to keep it a secret from her, but I didn’t. So I agreed to fight back and she helped me sign up for karate lessons to teach me self-discipline and self-defence. I used that karate all my life and have continued fighting bullies throughout high school. However, I also learnt the discipline to walk away from fights, bullying and hyper-masculinity by developing a healthy ability to entertain myself through imaginative play by reading some of Roald Dahl’s books as a child. Whenever the boys started playing soccer in the street or getting too rough for my liking, I would quietly retreat home and bury myself in Matilda or James and the Giant Peach or Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory - whatever I could get my hands on to avoid kicking a ball.

What sparked your interest in creating art? Your grandmother taught you traditional Xhosa beading, if I’m not mistaken?

When I was in high school, I actually wanted to become an Industrial Designer and while other kids followed their favourite bands or sports stars, I was mildly obsessed with Chris Bangle, who was the Head of Design for BMW at the time. I had pictures of BMW’s all over my bedroom walls and even inside my wardrobe and I bought the CAR magazine religiously. It was only when I got to university that I realised that that wasn’t going to happen on my terms and I was forced to do a foundation course in Art & Design in 2006, which opened up my eyes to the complex and multi-faceted world of the visual arts. In that year, my interests drifted between Industrial Design, Architecture, or Graphic Design because a career in Art was far too scary to consider. It was only when I had to make a decision about which direction I really wanted to take in second year did I confront myself about my dislike for mathematics and rigid rules and that is when Fine Art became my only option.

Yes, you’re not mistaken. However, my (paternal) grandmother taught me traditional beading AFTER I left art school (University) and I wanted to make use of glass outside of the glass studio. It’s almost as though I was destined to become an artist trained in a material my grandmother has used her whole life even though she’s not educated and my education has filled that gap between us. Whereas she understands how to work with beads in the traditional way Xhosa people have done for centuries, I understand the beads as glass and how glass interacts with light as an active ingredient but also how to work with it and stretch it ways Xhosa people have not yet imagined.

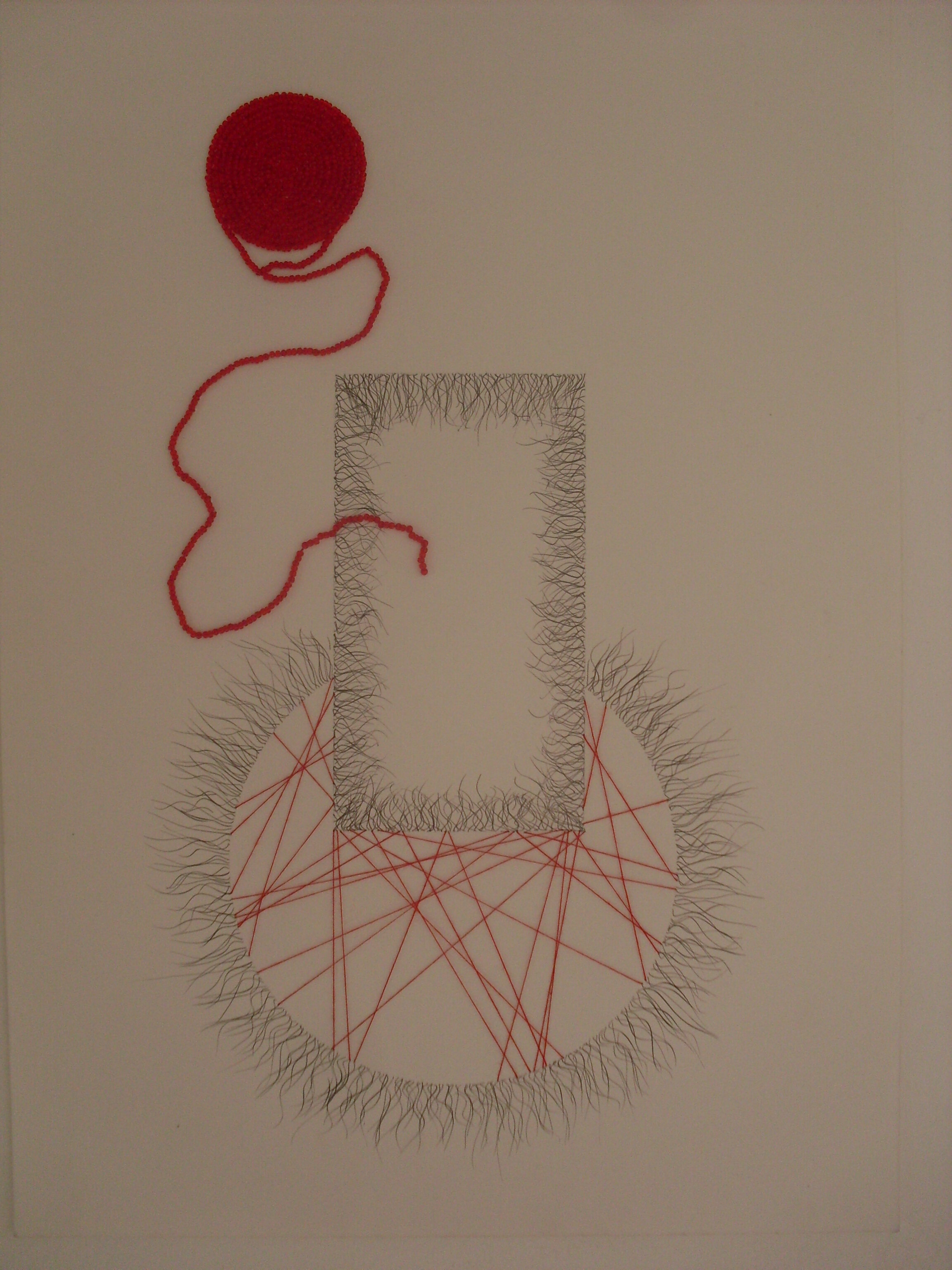

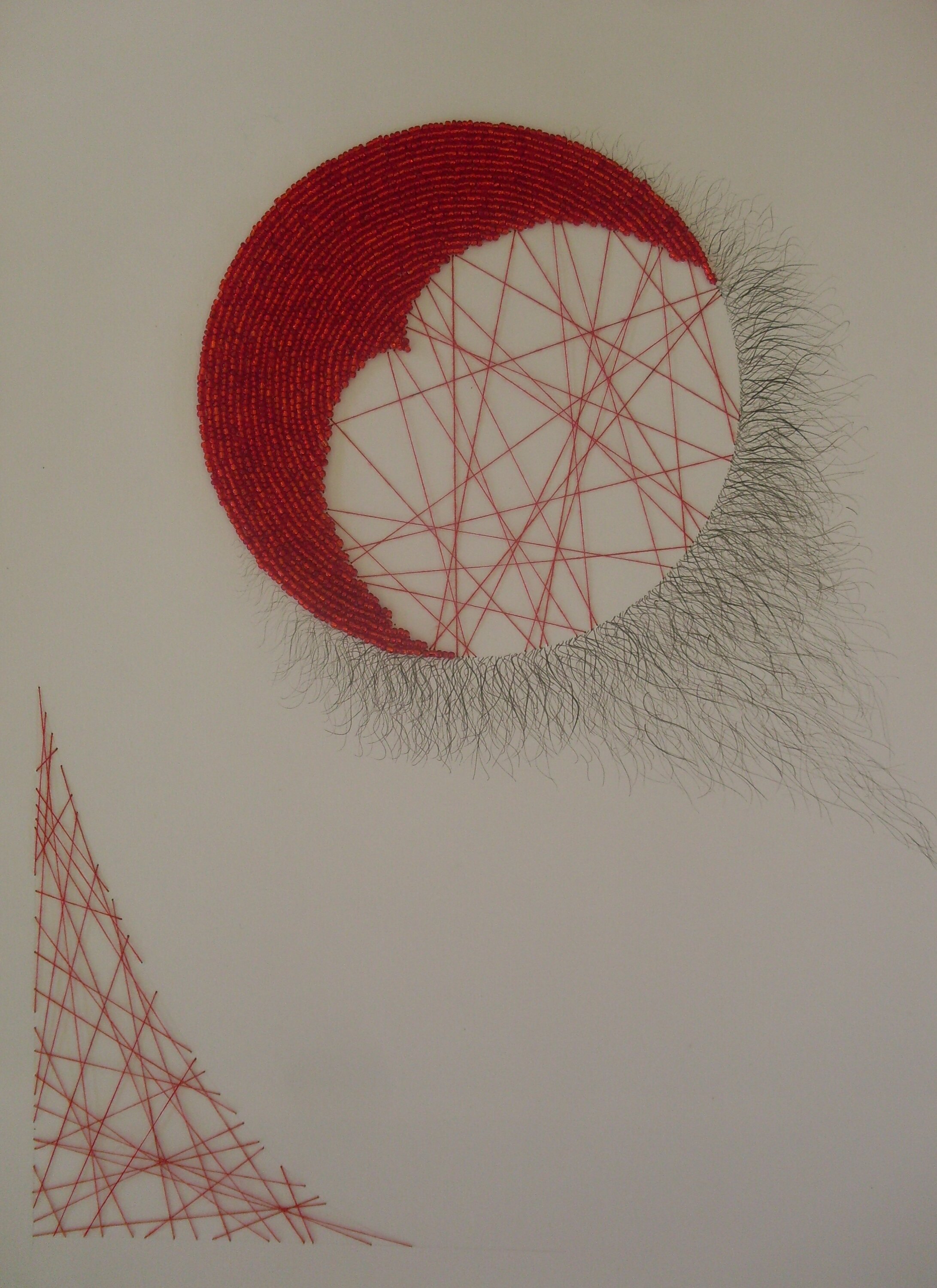

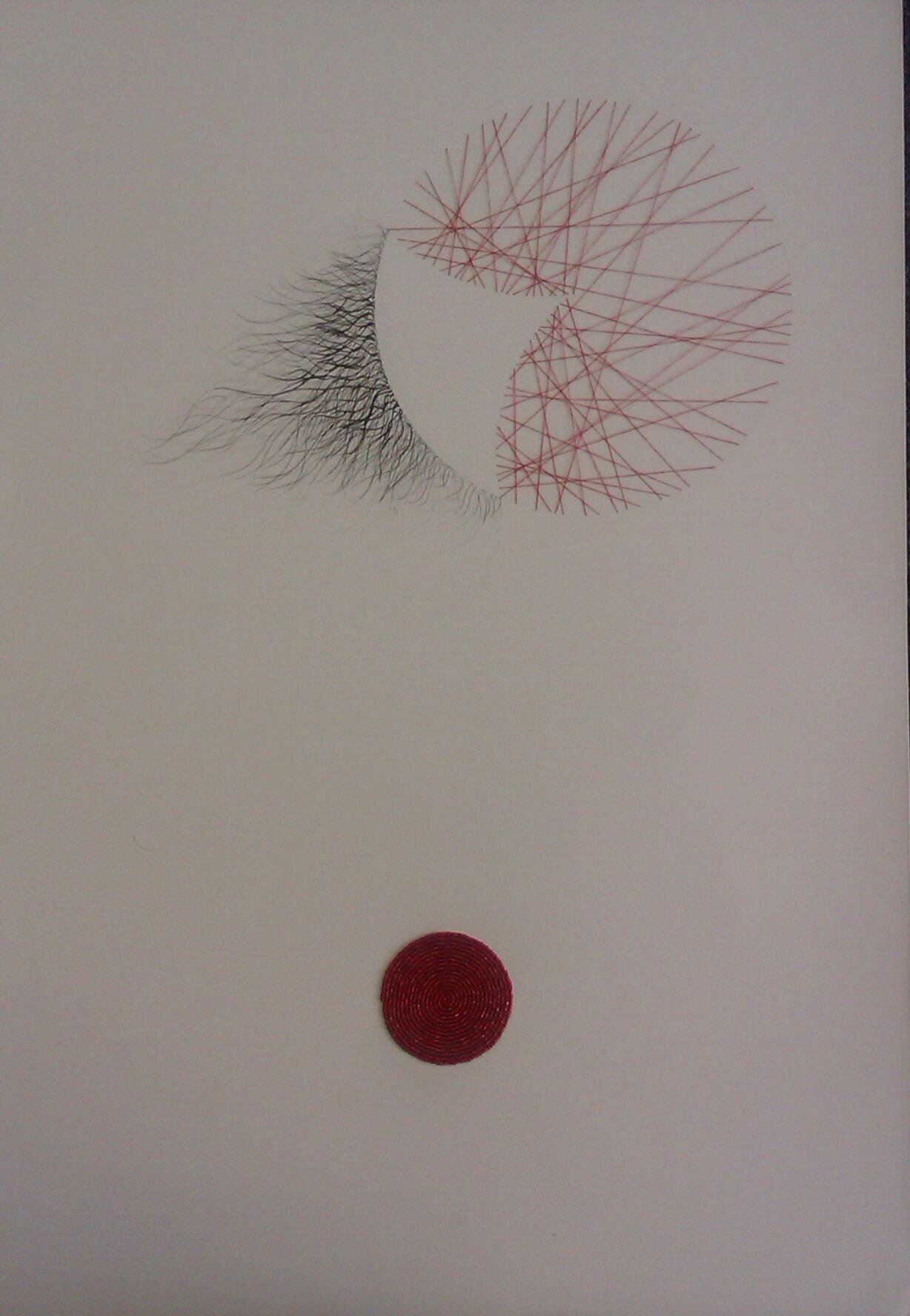

From Bongani Njalo’s Shapes of My Soul series:

Before studying art and creating work professionally, is there something you created that you consider your first piece of art?

That bowl I mentioned earlier that I made for my grandmother? That’s definitely the first work of art I ever made. The fact that I called it ugly doesn’t mean I don’t like it and that’s what I love about Art. The fact that you think something is beautiful or ugly, doesn’t take away its magic.

You received your National Diploma in Fine Arts from the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University majoring in stained glass- what drew you to that specific medium?

I chose Stained Glass because I knew that it’s a unique medium that isn’t as popular as painting, sculpture or printmaking as a chosen field, and so that meant that there is far more opportunity for me to stretch and explore my creativity, the medium and those limitations, if any.

You’ve since gone on to become a multi-dimensional and multi- disciplinary artist and performer- why is it important for artists to learn different “languages”, as you put it in an interview with Mamba Online.

I think it's important for artists to learn different languages because each language carries with it some form of limitations that another language can succeed better in dealing with. Also, from the onset of my career, what I understood was that I wanted to create experiences for people to deal with as opposed to products that consumers can tuck under their arms, take home and hoard. I don’t want my work to be hoarded; I want it to live in the memories of people from different perspectives in different places because that enriches the work for me. And I quite enjoy how the ‘artwork’ changes in performance as you take it from place to place and are challenged to deal with spatial constraints, socio-political issues and climate.

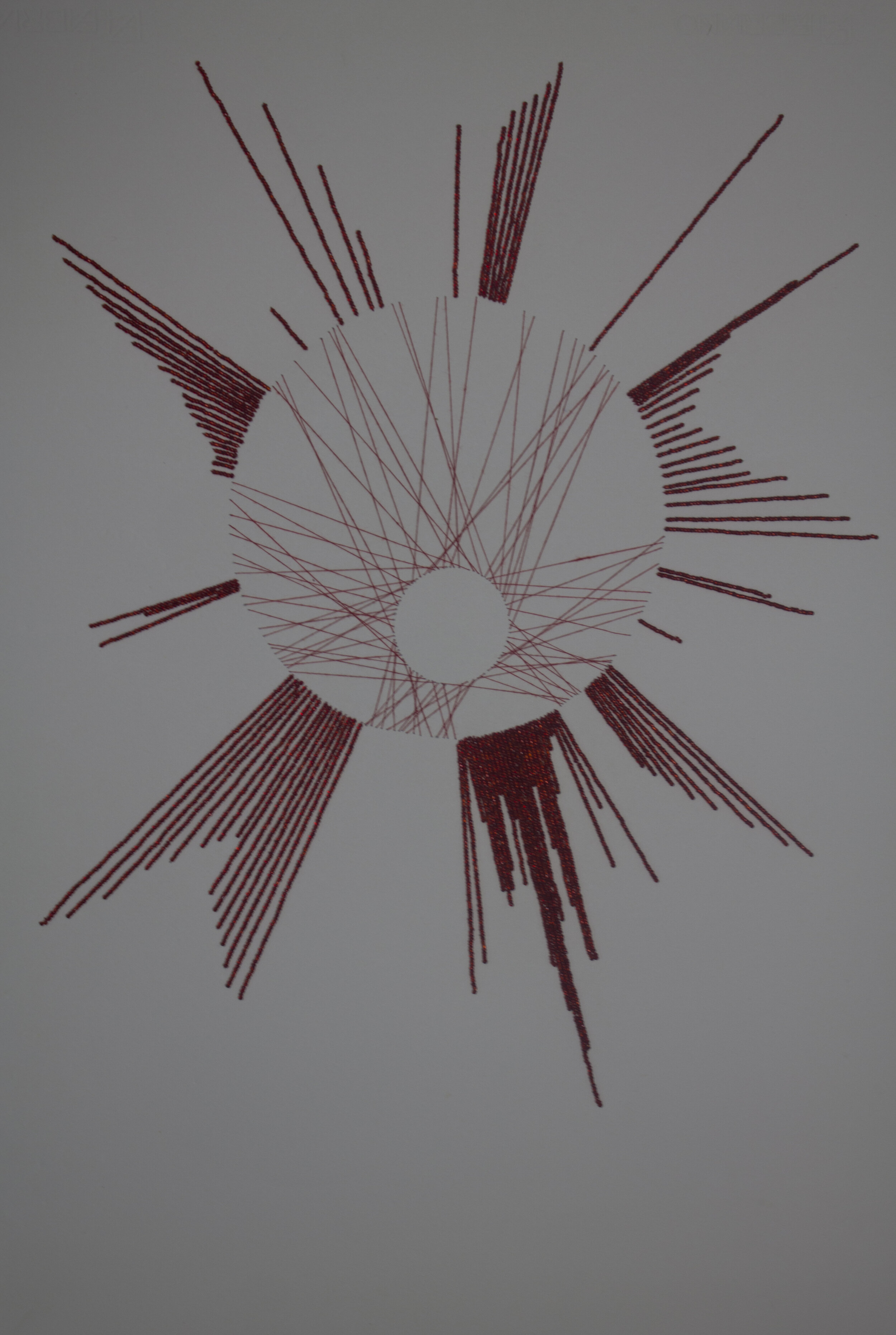

Bongani Njalo/ The Undoing of Soga (2017).

Your work Daddy’s Lap (2012) is incredibly striking, disturbing and heartbreaking- what you can share about conceptualising and executing it?

I wanted to work around the idea of invisible walls, fragility and vulnerability. The work deals with violence in the home which is more often than not; perpetuated by the father figure and how his presence looms in every dark corner of the house.

Performance art is also a big part of your career- would you agree that installations, interventions and public performance art are a great way to democratise art?

Totally! The perks of performance and intervention are that I don’t need to depend on a gallery to get an audience or commercialise my work. The gallery system can be quite restrictive and even impossible for the performance artist to work within because ‘they’ are looking for products to sell but that’s not why I make art. The economics are important, but if that’s all that I’m focusing on then, I risk losing integrity in my practice. I’ve always felt the need to take my work to the streets, to the people because the confines of the gallery space force people to think in a particular way, view themselves in a particular way. I find it such a pity that festivals like ICA’s Infecting the City aren’t as common and wide-spread as I’d like because accessibility to the arts and arts education are one in the same thing, and local artists are always complaining that there simply isn’t enough being done to educate communities about the arts and that galleries and theatres exist in spaces of the privileged.

“The gallery system can be quite restrictive and even impossible for the performance artist to work within because ‘they’ are looking for products to sell but that’s not why I make art.”

Speaking of installations, you collaborated with Phumulani Ntuli for He Does Not See With His Eyes (2013). The work, in part, is about “an opening of the mind's eye, allowing the individual to attain a higher sense of conscious awareness with the universe”. Why is this message important to you?

That work has actually become even more important to me now more than ever as we witness events around the globe that force us to be more aware of the fact that we don’t live in isolation and that all of our actions affect others. The coronavirus is a great example of how the butterfly effect works and how intrinsically we are tied to one another, so the work calls for each of us to aim for high levels of self-awareness, to know and understand that we function in an interconnected web. Each and every one of our actions has an effect or affect on another.

Bongani Njalo in a 2018 re-staging of He Does Not See With His Eyes:

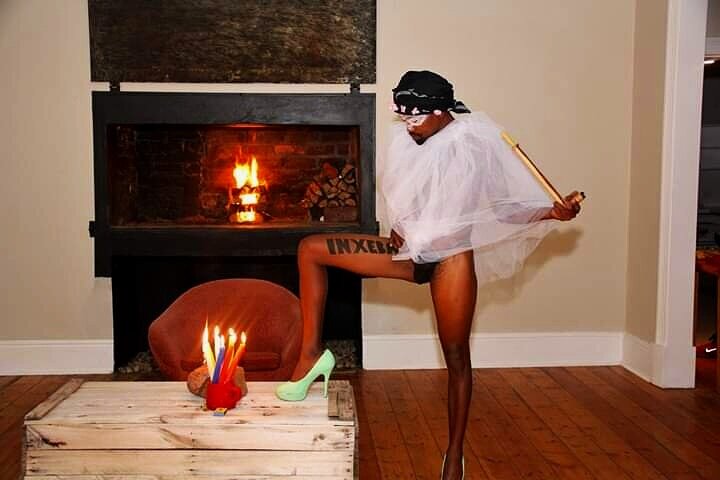

Abafana Abafani, which was in response to the banning of Inxeba, was very controversial. Were you hesitant to challenge and explore the masculinities in Xhosa culture?

Well, I’d say hesitant is an understatement because the truth of the matter is that I was shit-scared and worried about my safety. However, what I knew is that the work was very necessary and that trumped all my fears. I have also been thanked by a surprising number of black heterosexual men for making these explorations and challenging toxic masculinity head-on and that (for me) validates the work because they are my primary target audience. I will forever reiterate that Abafana Abafani is a work aimed at unearthing the diversity of masculinity and gender expression because parts homophobia is also deeply rooted in the misconception that masculinity has to be one dimensional and men believe that more than anyone else in society and they want to protect that fiercely.

What would you say are some of the biggest challenges South African artists- specifically queer POC artists- face?

While our rights and freedom of expression and all those wonderful things are enshrined in our beautiful constitution that does not protect us from homophobia and transphobia that exists in government offices. For instance, if I wanted to get a grant to further develop and tour Abafana Abafani from the provincial arts council in the Eastern Cape (the most homophobic province in the country), do you think I would succeed? Let’s take a moment to reflect on the CULTURAL landscape of our country for this. South Africa is a conservative society and our administrative and financial institutions in the arts are occupied by individuals who don’t have a good comprehension of artistic endeavour, its importance and value, and they consider the arts as a form of entertainment. Now, when people don’t understand your work and its value within a conservative and generally homophobic society, this presents all sorts of economic challenges that are potentially catastrophic for queer artists of African descent and of colour. The problem is that Africa is a place where decisions are still based on tradition and one's obedience to it and those in power employ this approach in a dictatorial style because the majority of them are not of our generation and they do not understand our struggles and the world we live in. My work is unashamedly intersectional and this can be very tricky on the African continent because I am constantly working towards the idea of a decolonised state of being and almost everything that I do challenges the way in which people understand themselves and navigate the world from the black African perspective. And I will be bold enough to say that I believe this is the shared struggle of queer black artists in Africa, not just myself.

Lastly- how do you envision your legacy as an artist and performer?

I’d like to leave something far more significant than an impressive body of work. I’d like to create and leave a place behind that I envisioned back in 2017 when I was in the U.S. as part of the Mandela Washington Fellowship. I am working towards creating a pan-African sculpture park that would be located in Port Elizabeth. I say ‘pan-African’ because all the artworks in the park would be created by artists from each of the 54 sub-Saharan countries in Africa, and these artists will work with local creatives to develop an artwork that reflects the culture of the visiting artist. This can be achieved through a ten-year long residency programme that effectively benefits multiple local industries and supports the local creative and cultural economy which we all know is rich with talent and scarce with resources and opportunities. I obviously can’t do this without political and private business investment, so I am pursuing my Masters in Arts Policy and Management at Birkbeck University of London through the Chevening Scholarship, which I have recently been awarded. There are various reasons why this dream is stretched out over the next two decades and partly the political instability in this city has forced me to hold back, and factors like my lack of adequate educational/academic strength and confidence to see this through.

I’d like this ‘place’ to become a place of reflection, celebration and healing.